Embrace the Unknown

- Jul 10, 2020

- 4 min read

“Do you think it’s possible that humans will ever evolve beyond war?” I asked, casually sprawled on the dorm lobby sofa.

Mike’s response was a swift, flat-out “No.”

“Not even in a thousand years?” I pressed.

“No way.” He replied with an air of masculine certainty.

“What about ten thousand years? I mean, it’s human nature to evolve, get smarter — and it will be a matter of survival to eliminate war.” I’m sure Mike saw the words “naïve idealist” flash across my forehead, but I thought I’d made a good point. However, he refused to even entertain the possibility. And after two dates, I knew we’d never become an item.

In hindsight, I should have cut him some slack, especially since this conversation happened during an intense period of the Cold War. The Day After, a TV movie about the horrible aftermath of a global nuclear war, had broken all ratings records. And another hit movie, War Games, had delivered its unforgettable line about how to extract ourselves from a nuclear deadlock: “The only way to win is not to play.”

It’s easy to see why someone in the mid-1980s wouldn’t consider world peace possible, given that fear of nuclear annihilation was in the air and on the airwaves. But any period during one of the most violent centuries in history could easily lead one to that conclusion. With continual military conflict, media rife with tragic war heroes, and bowing to classic literature like Lord of the Flies, why wouldn’t Mike assume the inevitability of a bleak future? After all, we form our beliefs largely from what we’re taught and the cues we receive.

But what about all the possibilities and alternative outcomes we don’t see and we don’t know? Like the true Lord of the Flies story that happened 50 years ago: instead of the warped divisiveness that led to cruelty and murder in the fiction novel, the opposite happened with the real-life teenage boys! Fifteen months stranded on an island south of Tonga and their nature was to cooperate, be truthful, and stay focused on the goal of getting rescued. If the actual Lord of the Flies story were in our generational zeitgeist, maybe we’d all be more inclined to believe in the possibility of a harmonious world.

I suspect that a big part of why the boys on the island of “kind humanity” *did* survive was because they were off the grid. They weren’t picking up on the stress signals emanating from 20th-century airwaves: no fear-inducing news stories, or adults giving off a vibe of “life worries.” They had their own stress to be sure. But on a deserted island they had no choice other than to connect with nature and at some level tune into all the “unknown unknowns” swirling around them. And among those unknowns, they held onto the idea that they would be rescued.

Could we take a cue and do the same? Is it possible to acknowledge the chaos and insanity churning in the world today — a pandemic, festering systemic racism, and a dysfunctional US government, to name a few — and still hold a belief that we shall overcome? It takes effort, but I believe we have the power to cultivate a mindset that can guide us out of this mess. It requires regularly going to one’s own metaphorical “deserted island” and detaching from the relentlessly negative external cues. It requires finding one’s own version of a hopeful vision and protecting it, much like how one shields a flame so it doesn’t blow out in the wind.

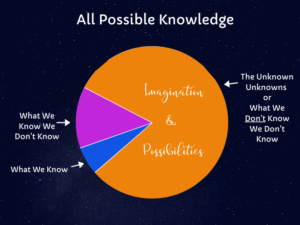

This is not a Pollyanna view, though I get why it might be taken that way. I’m not saying we should deny the tiny pie piece of “things we know” or the other narrow slice of “things we know we don’t know” as depicted in the diagram. We need to acknowledge the range of problems we live with and look to those who have more knowledge than we do on a particular issue. But we’ve all gotten too comfortable with those two little pieces of the pie at the expense of the third, largest piece.

It’s that enormous portion of “unknown unknowns” which holds the key to a harmonious collective future. If we spent more time there, in the universe of imagination, then we’d nurture and grow the realm of possibility. Sure, it’s easy to imagine the unknown possibilities of dystopian horror films. (We are quite accustomed to going there.) But it’s within the “unknowns” that we’ll find a cure for Covid and every other pandemic that lurks. That’s also where viable scenarios emerge for a world without racism, and a million ways to build equal opportunities and health care for all. It holds strategies for world peace with a functioning government, or with no government at all.

There’s an infinite universe of good things that the “unknown unknowns” contain — but they can’t enter our conscious collective if we stay focused only on the tiny portion of “what’s known.” Like the real-life boys on the island, if we nurture the hope of a positive outcome, we diminish the odds of self-destruction.

Looking back, I understand why I didn’t want a third date with Mike. I wanted to keep my little flame of hope from going out and I must’ve instinctively known it would be more difficult if the unspoken belief around me was “no, the ideal is not possible.” Instead, my instincts led me to a life partner who treasures my purposeful imagination. We are each other’s anchors of realistic optimism, even during these challenging times. We value “glass half-full” thinking and proactive choices. We train each other to keep our individual flames shining, something anyone can do with a little effort. And herein lies the key to an ideal world, or Peace if you will…

For You, for Me, for Anyone who likes the idea of the best possible life for all: We reach into the universe of “unknown unknowns” and conjure a hopeful and sustaining feeling or vision for the future. We sidestep cynicism because deep down we know the power of imagination is woven into our DNA. And then we protect those hopeful sparks as if our lives depended on it… because in a way, they do.

Because I feel it’s important to back up words with action, I choose a nonprofit to support with each post. Building a movement toward world peace is no small task, but find out about a top-rated organization that does it well in Becoming People Who Promote Peace.

Comments